The category number

A common joke is that everyone has a minimal number \(n\in\mathbb{N}\)

such that, if someone mentions an n-category,

one stops thinking. My personal number is maybe \(n=2\):

afterward my pet example “n-dimensional cobordisms embedded into an

n+1-dimensional-space” (see below) gets quite hard to imagine

(left aside the problem to draw these cobordisms).

Let me give now some more details.

Let me be a bit sloppy

I must

admit that I tend to be quite sloppy with the notation of

an n-category. To be more precise,

I should write \((n,n)\)-category instead

of n-category, i.e. I never assume that higher

morphisms are invertible.

But I am even sloppier sometimes, i.e. if I speak of an n-category

I tend to ignore the difference between a weak and a strict n-category.

Note that in case \(n\leq 2\) this can be (sometimes) justified by a corresponding

coherence theorem.

I am also very sloppy when it comes to more fundamental set theoretical and logical questions, e.g. the

subtleties one needs to define the “categories of categories” and related concepts.

Much more details, e.g. a discussion of weak and strict n-categories,

can be, for example, found in Leinster's book here.

A rough description

The idea behind higher category

theory is easy to explain. It is a generalization of category theory, which can be

seen as generalization of set theory.

The slogan for me is that a category is a collection of “set like structures”

with the category of sets as a blueprint example. A 2-category is

a collection of “category like structures”

with the 2-category of categories as a blueprint example. A

3-category is

a collection of “2-category like structures”...

Imagine a set as a collection of points (aka \(0\)-cells),

then a 1-category, also know as category, is a

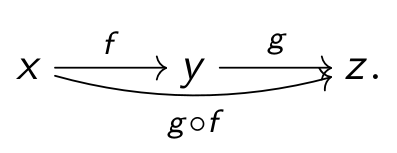

one-dimensional structure connecting the objects with some one-dimensional cells called morphisms. The usual

notation for this is

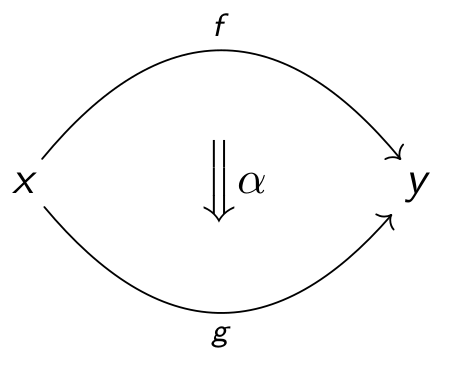

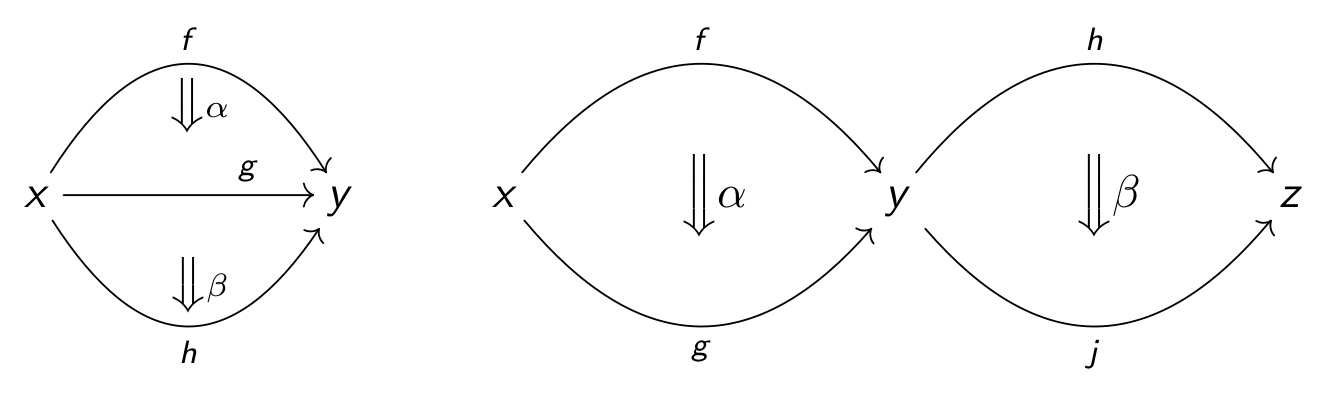

For example, if one starts with a usual category, then one can add two-dimensional cells between the one-dimensional cells and one gets a picture like

Some basic examples of (strict and weak) 2-categories are:

- The 2-category of categories CAT, i.e. objects are categories, 1-cells are functors and 2-cells are natural transformations.

- The Bimodule 2-category BiMOD i.e. objects are rings \(R,S,T,\dots\), 1-cells are bimodules over two rings \({}_RM_S,{}_RN_S,\dots\) and 2-cells are bimodule homomorphisms. The one-dimensional composition is given by “tensoring over the middle ring” (e.g. \({}_RM_S\otimes_S{}_SN_T\)) and the two-dimensional compositions are standard composition and “tensoring of morphisms”.

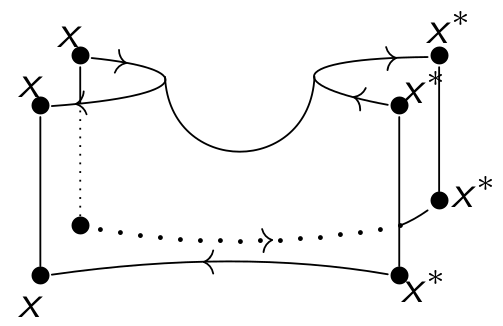

- Two-dimensional cobordism 2-categories, e.g. one can

take points as objects, one-dimensional cobordisms as 1-cells and

two-dimensional

cobordisms as 2-cells.